“Reader, I went through a wedding ceremony with him”: Translating Jane Eyre

Literature gets translated into many languages. But what can we learn from these translations – especially the very many translations of a book like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre which has been translated innumerable times into at least 25 languages?

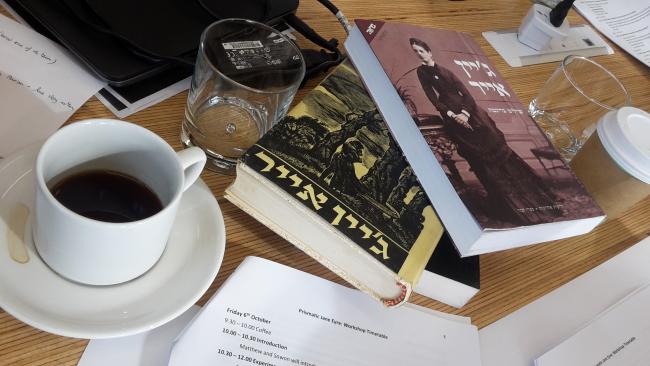

In October 2017 researchers from across the globe came together at St Anne’s College in Oxford to discuss various transmutations and translations of the revered novel, first published under the pen name Currer Bell in 1847. A bildungsroman (a coming-of-age story), the text follows the trials and tribulations of the novel’s eponymous heroine, and is widely regarded as an English classic that revolutionised the art of fiction in many ways.

At the workshop, Prismatic Jane Eyre: Close-reading a global novel across languages, this band of researchers explored the novel’s rendering in a myriad of languages. Arabic, Hebrew, Modern Greek, Polish, Mongolian, Tibetan, Korean, Spanish, and French are just a few of the diverse languages that were represented at the workshop. The workshop was structured as an alternation between segments of multilingual close reading and discussion in which the general issues arising from the readings were probed. Through a comparative close reading of parallel passages, the researchers noticed textual variations and departures. One of the explicit aims of the workshop was to discover what can emerge from a comparative close reading of multiple translations, and to trace the factors that contribute to textual shifts and changes. The workshop not only offered some fascinating discoveries but laid the basis for a further workshop in spring or summer 2018 leading to a print or digital publication.

During the workshop, just one of the numerous instances where translation showed itself as prismatic, taking into account questions of cultural difference, socio-political concerns, and syntactic structures and semantic features, is Jane’s famous announcement: “Reader, I married him”. Probably among the most famous phrases in the English language, the statement can be back-translated into English as “Reader, we married each other” in the Slovenian text, while in Persian “Reader, he married me” is prevalent in all translations. Tibetan offers: “We got married/ I went through a wedding ceremony with him”, and older Hebrew translations, drawing on Biblical references state, “I raised him up”. All of these translations are varied renderings of Jane’s original assertion of agency.

Of course, Jane Eyre functions in manifold permutations: radio dramas, theatrical works, graphic novels, comics, art works, and films. (At the time of writing, Jane Eyre has just finished a run at the National Theatre.) At the workshop, certain researchers drew attention to Jane Eyre’s iteration into other media in several languages, and how the text has disrupted binaries of low and high culture. In Korean, in high culture, Jane Eyre is a story of personal triumph in line with Confucian ideals, while in pop culture it is a love story. For the researchers, snippets of the Bollywood 1952 movie Sangdil, in which Rochester sings to Jane, made as much of an impression as the Japanese graphic versions of Jane Eyre, which were inspired by European illustrations. A modern Greek comic of Jane Eyre, published in 1951 in the popular demotic Greek, presents the traditionally swarthy and plain Jane as a sexy blonde bombshell.

Since Jane Eyre was first published in 1847, it has never been out of print. There is something about Jane’s individualism, the novel’s critique of class, gender, and religion, and its infinite scope for (re)interpretation and translation, that have made the novel so globally successful. In the workshop it became clear that the text as manifested in various languages points to multiple signifying possibilities and plurality intrinsic to translation, which makes it the perfect focus point for the Prismatic Translation strand of the Creative Multilingualism project.

Eleni Philippou is a Post-doctoral Researcher on Creative Multilingualism's 6th strand: Prismatic Translation.

Researchers in attendance were:

Rebecca Gould (Birmingham – languages of the Caucasus)

Alessandro Grilli (Pisa – Italian)

Yunte Huang (UCSB – Chinese)

Madli Kütt (Tartu – Estonian)

Emrah Serdan (Istanbul – Turkish)

Adriana Jacobs (Oxford – Hebrew)

Claudia Pazos Alonso & Ana Marques dos Santos ( Oxford & Lisbon – Portuguese)

Ulrich Timme Kragh, Abhishek Jain & Magdalena Szpindler (Poznan – Tibetan, Hindi, Mongolian)

Jernej Habjan (Ljubljana – Slovenian)

Céline Sabiron, Léa Koves & Vincent Thiery (Lorraine – French)

Sowon Park (UCSB – Korean)

Yousif Qasmiyeh (Oxford – Arabic)

Eleni Philippou (Oxford – Greek)

Yorimitsu Hashimoto (Osaka – Japanese)

Kasia Szymanska (Oxford – Polish)

Andrés Claro (Chile – Spanish – Chilean/Latin American/Peninsular)

Marcos Novak (UCSB – digital media)

Richard Rowley (Oxford – digital media)

Tom Cheesman (Swansea – digital media)

Where next?

Find out more about our Prismatic Translation research strand

New British Academy report highlights importance of language skills

Inspiring pupils: multilingual creative writing