Poetry in Translation, Poetics of Translation

How can translation make an ancient text speak to present day experiences? Bereavement is universal, but the expressions of loss differ widely, perhaps because loss itself is of various types.

Separation from, life-changing injury to, and death of loved ones all cause visceral pain, in addition to emotional rage, and provoke an existential quandary. However, each culture determines and guides how loss is managed and expressed. For Marlé Hammond, the elegies of al-Khansa’ are not only a woman’s lament at the loss of her heroic brothers to enemies and violence, but also her insertion of woman’s voice into the fabric of a long tradition of men’s poetics in the Arabic language and literary tradition.

James Montgomery on the other hand finds in the same elegies a language for his own loss, or losses, and in the process rediscovers in what he at one time saw as dated conventional expression the poetics of loss that speaks to us even today. In Hammond and Montgomery’s hands, alien poetics comes to be our own. Al-Khansa’s elegies are alien in two major ways from our perspective: they are ancient; and they are expressed in Arabic, a foreign language. Translation gives them a new currency.

Translation can be the means through which alien poetics speaks to us, but only if it is transformed, in this instance, into our own language of loss. Montgomery’s renditions, which recreate his own scenarios of loss, move us so deeply because they capture in a very visceral way the intensity and rhythm of our pain and its rage. The lamenting woman in al-Khansa’s elegies perform on our behalf the drama of bereavement—the changes occurring to our bodies, the ideas racing through our minds, and the actions we take in the everyday madness of our grief.

Listen to James Montgomery reading his translations of al-Khansa at a recent workshop:

Hear James Montgomery in conversation with Marina Warner and Marlé Hammond, discussing his publication Loss Sings:

Prismatic translations from the workshop

1.

All night long sleepless my bleary eyes ringed with coal/kohl

Sleep won’t come, I’m staring, eyes gritty, salt-scoured, endless vigil

Sleepless, I wore out the night in vigil, my eyes adorned with shadows

I woke and passed the night sleepless as if my eyes were rimmed with sand

2.

A. Watching stars I was not tasked to watch, wrapping myself at times in remnant rags

B. Tossing and turning in the twisted sheets

C. Tending the stars, but not told to tend them, shrouding myself at times in remnants

D. I watched the stars I was not asked to watch and wrapped myself in the end of rags

3

I heard news I had no pleasure in

The news came, terrible, “I have news I must tell you, what will you say?

I had heard what ended my joy, one who came to repeat a story

Then listened and was not made glad of it, to a man that came betraying the news

4.

C. “Sakhr inhabits the grave between the stones”

B. He told me “Rock into rock, laid under stones

D. He said, “Sakhr rest there in a grave, knocked down in a tomb between the stones”

5.

C. Go my brother may God keep you near, turning from injustice, seeking revenge

D. So go brother, and may God not be far from you, a man who leaves injustice and seeks revenge

B. Leave me, linger, leave me, linger

6.

D. You used to carry a heart that wasn’t unjust, firmly set in a rowdy lineage/ that wasn’t obedient

7.

D. The night illuminated his form, like an arrowhead, in bitterness, freedom and son of the free

B.You, finest of fine men, bright spearhead, of a line never enslaved

8.

D. I will make you cry not lamenting the dove? The night stars are not for travellers

9.

D. I won’t reconcile the group you warred with until the return of white to the black cooking-pot

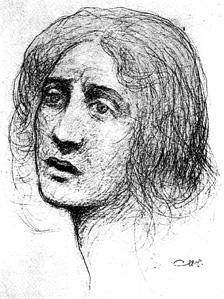

Main image by Kahlil Gibran - http://www.al-funun.org/al-funun/images/, Public Domain, Link

Where next?

Finding poetry in a new language