The Cave: a multilingual, multimedia opera

The Cave (1993), a multimedia opera by composer Steve Reich and video artist Beryl Korot, tells the story of the life of Abraham as it is given in religious texts and how it is interpreted by modern accounts given by individual members of three different religious and cultural backgrounds – Israeli, Palestinian, and American.

The cave of the title refers not to the Platonic cave as one might assume, but to the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron where it is believed Abraham, Sarah, and other major religious figures like Adam and Eve are buried: a place sacred to Jews, Muslims, and Christians alike. The opera integrates and in many ways is derived directly from interviews taken with Israeli, Palestinian, and American subjects who were asked to answer questions like, ‘Who is Abraham?’, ‘Who is Sarah?’, and ‘Who is Isaac?’. These filmed interviews are integrated with a live musical performance, alongside documentary footage of the Cave of the Patriarchs and the surrounding area.

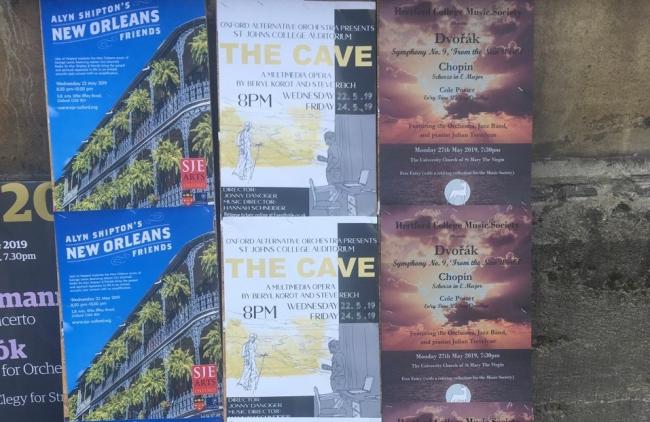

The Oxford Alternative Orchestra, led by conductor Hannah Schneider, gave two performances of The Cave in late May, with production by Jonny Danciger. I was very fortunate to be involved with this project as one of the quartet of singers making up part of the orchestra, and given that I am a musician who studies opera academically with a particular interest in text and language, I was especially drawn to the unusual yet highly fruitful ways in which Reich and Korot used text and language in The Cave.

Spoken language – its nuances, its inflections – has been a critical part of Steve Reich’s work and career, and The Cave makes spoken language the foundation not only of the opera’s presentation, but also its music. While clips from the individual interviews are played as recorded, they also serve as the point of origin for musical phrases given to the singers and instrumentalists. On a practical level, this element made rehearsing The Cave a particular challenge as the orchestra had to match exactly the rhythms and contours of the filmed interviews so that the music would flow seamlessly with the projected video. The final effect, however, made for a dynamic interplay between live music and film unlike anything I’ve ever performed or experienced. As the opera developed, the connection between the documentary footage and the music became ever more interconnected, so that by the third act there was no differentiation between ‘film moments’ and ‘musical moments’.

By dividing The Cave into three sections which tell the story of Abraham from the Jewish, Muslim, Christian perspectives, Reich and Korot create a sinuous sense of drama. The audience hears the same ancient tale told in three very different ways, so that the story seems to double back upon itself, highlighting discrepancies and divergences in the three traditions while at the same time emphasising the central shared tradition. In Korot’s documentary footage, this element of the new-yet-familiar is given further emphasis through multilingualism. Both Act One (the Jewish) and Act Two (the Muslim) include longer clips of religious leaders reciting texts in Hebrew and Arabic. This allows the Abrahamic story to be told in its original, sacred contexts, but also anchors the audience in the traditions’ inherent multilingualism.

Listening to the history of the kings and prophets in Hebrew and Arabic provides a clarity that, paradoxically, an English translation cannot, and more importantly allows practising members of these faith traditions to tell their own story. Indeed, the entire practice of using the spoken interviews as basis for The Cave’s music allows each interviewee to reach the audience directly through both the visual medium of film and the aural medium of music.

What Reich and Korot are doing, therefore, is ‘translating’ the story of Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Ishmael, and Isaac through different faith traditions while celebrating the pluralism inherent in re-telling such an ancient tale. By centralising spoken language through the video projections, interviews, and in the very structure of the surrounding music itself, Reich and Korot emphasise the multilingual and multimodal ways in which the Abrahamic story has been passed down through the generations.

Our particular production sought to emphasise the continued impact of the Abrahamic tradition by including a silent actor playing the role of an anthropologist researching the three Abrahamic faiths. Having her react to and interact with the videos and music helped to bring a work from 1993 into the present, especially when continuing political and religious tensions highlight the need to seek out and celebrate shared points of origin.

As a music scholar with a particular interest in opera and text, The Cave made a fascinating piece of study; as a performer, it made an exhilarating challenge. It was a privilege to work with such a hardworking, talented, and open group of musicians on this project, and I hope dearly that the success of The Cave will enable the Oxford Alternative Orchestra to further push the limits of what a student ensemble can do. Watch this space!

Margaret Frainier is a Creative Multilingualism DPhil candidate researching the development of Russian opera libretti from the late eighteenth century. She is part of Creative Multilingualism's 4th strand: Languages in the Creative Economy.

Where next?

Why Yorkshire, Cockney & New York accents aren’t out of place in Iannucci’s ‘The Death of Stalin’